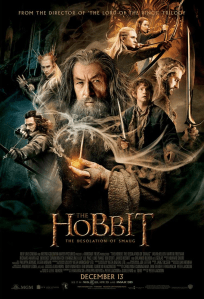

Release Date: December 13th, 2013 (UK/US)

Genre: Action; Fantasy

Starring: Martin Freeman, Ian McKellen, Richard Armitage, Benedict Cumberbatch, Orlando Bloom, Evangeline Lilly

Peter Jackson’s carrot-wielding Bree resident looks knowingly at the screen before sidling along the rainy, muddy Middle-earth town. Moments later the smoky, beer-filled room of the Prancing Pony inn hosts dwarf-heir Thorin as he glances wearily around clutching his axe in preparation for any potential attack. Gandalf the Grey sits opposite him, enticing us with familiar wispy tones, underplayed confidence and Lord of the Rings lingo (“We’ve been blind… and in our blindness the enemy has returned”).

We’re back. No, it’s not quite the Middle-earth from a decade ago — or, narratively, decades later — but it was never going to be. Rather, The Desolation of Smaug signals a return to the comfort of Peter Jackson’s pre-Lord of the Rings universe, and already proceedings seem more urgent than last time around.

Following their narrow escape from the Misty Mountains and temporary fending off of Orc war chief Azog, Bilbo (Martin Freeman) and his company of dwarfs find themselves splintered from Gandalf (Ian McKellen), who must investigate the state and whereabouts of an evil necromancer boasting powers that are ever-growing. As they part ways for the time being, Gandalf suggests that the best way to continue on their journey towards the Lonely Mountain and Erebor, is for the group to travel through a dishevelled, haunting forest, rather than treading two-hundred miles north and going around it. In the first film, the dwarfs and Bilbo most certainly would’ve taken the long route, and would definitely have sung an out-of-place song about picking mushrooms or making fire en route. Many of the previous instalment’s shortcomings (long-comings, even) are brushed to the side this time though, as the film hurtles along at a splendidly speedy pace, with plenty of action and wit to serve.

In fact, the variety of creature encounters and battle sequences give The Desolation of Smaug a much needed burst of energy from the get-go, unlike An Unexpected Journey which never really hit any kind of stride until Bilbo’s magnetic encounter with Gollum. Sadly Gollum does not feature here, however Bilbo does partake in a similarly dynamic conversation with Smaug the dragon, a meeting which is surprisingly full of more humour than tension. Martin Freeman comes into his own as the Hobbit Baggins, and along with a new found purpose through which his character evolves, Freeman also offers more than a handful of genuinely laugh-out-loud moments. His hurried, fidgety approach works expertly as he is often seen placing his cohorts before himself, exemplified during the tremendous barrel scene. However Bilbo’s engaging back-and-forth with Smaug sits effortlessly at the pinnacle of Freeman’s performance. Benedict Cumberbatch plays the dragon and, unlike Gandalf who possesses an assuring whispery tone, delivers his speeches deceitfully and slyly, as the words echo off the screen.

For a film (and trilogy) entitled “The Hobbit” we really could’ve done with more of said small being. At over two hours and 40 minutes (nine minutes shorter than the previous film) there is bountiful time for director Peter Jackson to tell the story of Bilbo finding the Ring and how the poisoned chalice affects him, however the film only breezes over the developing relationship between Hobbit and Ring. Rather, The Desolation of Smaug puts greater emphasis on the relationship triangle which incorporates a returning-to-the-franchise Legolas (Orlando Bloom), new-to-the-franchise Tauriel (Evangeline Lilly) and already-in-the-franchise Kili (Aidan Turner). The return of a makeup-laden Legolas is smart move on Jackson’s part as both the elf and Tauriel are the primary vehicles of energy, dispatched by way of exhilarating, fun-to-watch battle sequences; we even see Legolas skate via Orc rather than shield, as he did in The Two Towers. However unlike the romance sub-plot featured throughout the original trilogy (both book and film), the love triangle here feels very forced and artificial. Its creation was conceived exclusively for the big screen, but the film does not need it for added drama or emotion — that is already there as part of Bilbo’s journey.

The Desolation of Smaug is too long, although at no time does it noticeably falter as a consequence. There is more than enough going on to keep the audience attentive, and as a result the film looks more like a film than it does a congregation of set-pieces. Along with the reduced frame-rate (in most cinemas, back from 48 frames per second to 24) the swift advancement of proceedings prevents the viewer from becoming bored and spending their time staring at background objects that look exceedingly prop-like in a higher frame-rate environment — this hampered part one. The typically Lord of the Rings wide-shots which span over landscapes are beautifully shot and film’s computer-generated additions mesh in well. In an interesting move by Jackson, we see a number of mirroring scenes which serve both as a warning of evil times to come, and as a chance to reflect. For instance, Bilbo twanging the spider web and alerting many spiders a la Pippin knocking the metal armour down a shaft, in turn waking the goblins in Moria, and Thorin’s emphatic “What say you?” in his Aragorn-esque speech demanding affirmation, are two examples. Perhaps the most poignant of all though, is the elderly dwarf Balin’s declaration of his admiration for Hobbits, “It never ceases to amaze me, the courage of Hobbits,” which he unveils with the same authenticity as Gandalf does towards Frodo early in The Fellowship of the Ring.

Peter Jackon’s passion for the subject matter seeps through in abundance here and his decision to split the cinematic adaptation of The Hobbit into three films looks a great deal more justified by the end of The Desolation of Smaug (though there’s still a way to go). Martin Freeman shines as Bilbo Baggins in a sequel which, although still has its downsides, succeeds its predecessor both narratively and in content.