Release Date: September 10th, 2015 (UK); September 18th, 2015 (US)

Genre: Action; Science fiction; Thriller

Starring: Dylan O’Brien, Kaya Scodelario, Thomas Brodie-Sangster, Patricia Clarkson, Aiden Gillen

As a direct follow up to The Maze Runner, Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials grants director Wes Ball an opportunity to throw us straight out of the frying pan and into the fire. There is no time to catch up, no dialogue wasted on refresher exposition. You could stitch the final reel of the former onto the first reel of the latter and the flow would be seamless. It’s an approach that respects up-to-date viewers but also risks alienating franchise newbies; unlike the Divergent series, the lingo in this mid-franchise outing is harder to grasp — we suddenly learn of a virus called the Flare, a mountain-based faction who go by The Right Arm, and more about the horribly named corporate wrongdoers WCKD.

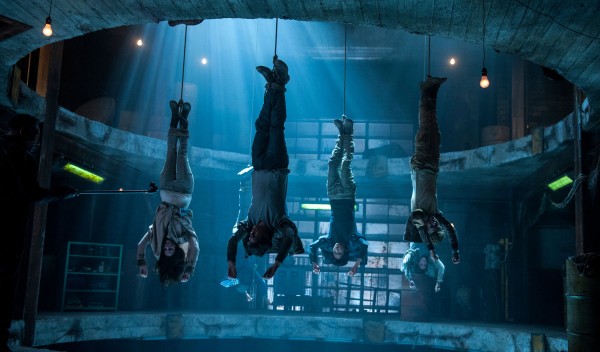

Aiden Gillen’s Janson, a facility head with an iffy demeanour, sets the scene: “The world out there’s in a precarious situation”. Perhaps the only thing less stable than civilisation is Gillen’s vacillating accent, though in fairness he does fund the film’s early uneasy air. Having escaped the maze, the Gladers — including Thomas (Dylan O’Brien), Teresa (Kaya Scodelario), Newt (Thomas Brodie-Sangster), and Minho (Ki Hong Lee) — find themselves holed up in a bunker eerily similar to the one run by Ava Paige (Patricia Clarkson) in the last film. Free from seclusion, freshly cooked food, their own bunk beds. It’s as if everything is too good to be true.

Only, in reality, nothing’s good anymore. The world outside, aptly rechristened the Scorch, has been ravaged by heat and disease. Zombie-like creatures called Cranks roam freely in search of flesh to chew on. A step up from the maze beasts, these clambering speedsters evoke a 28 Weeks Later vibe, especially as they are positioned within a climate of militant command and clinical action. Thomas, in spite of all this misery, manages to muster up some rebellious positivity. He is the eternal optimist in a pessimistic world.

Maybe they see a ray of hope radiating from Thomas in the wake of his stubborn idealism, but people do trust him too easily and this undermines the credibility of the story. Aris (Jacob Lofland), a loner who spent time in another maze before the bunker round-up, opts to collude with Thomas despite not knowing him. It is a theme throughout: our hero is heralded as a morally, physically, and mentally infallible being. When the group come across a refuge disguised as a dumping ground for old garments and rusty equipment, they all take the opportunity to dawn suitable Scorch clothing. Apart from Thomas, who discovers a suave jacket among the dross, something that could have graced Ryan Gosling in better times.

It’s as if all the others know he is the film’s central star. Fortunately none of this canonisation really matters because Dylan O’Brien is such a charismatic and inviting screen presence (a less capable frontman might’ve been insufferable given the circumstances). The film is arguably at its most compelling during those rare moments when Thomas does have to confront vulnerability. There’s an animosity at the fore, driven particularly by Teresa who begins to question her counterpart’s role in bringing about rebellion. Are they doing the correct thing by evading WCKD? Was the Glade as good as it was ever going to get?

Regardless, we know WCKD boasts an immoral underbelly. Towards the beginning, Thomas and Aris find out that Janson’s apparently safe retreat is actually a giant-shrimp-breeding-cum-human-blood-harvesting factory controlled by the aforementioned organisation. It may be a source material problem, or an issue with mainstream popcorn fiction in general, but the narrative occasionally lacks plausibility. Aside from the Thomas trust issue, even more blatantly obvious coincidences rear with jarring nonchalance: a revealing crisis conversation between Janson and Ava just so happens to occur in the company of Thomas and Aris on the night they break into the secret facility.

The message is clearly anti-corporation and anti-oppression, and T.S. Nowlin’s screenplay not-so-subtly channels that message via Thomas’ middle finger. These mature themes are matched by a horror-inspired underbelly that teeters right on the edge of a 12A UK rating. Fans of the Fallout video game series might mistake certain set pieces for similar looking locations in said game’s nuclear-torn Washington D.C. (an abandoned subway station springs to mind). Cinematographer Gyula Pados has more to play with here and the wider scope benefits Ball’s film greatly. Broken cities incite awe and wariness as they resemble the urban desolation shown at the end of Inception, while seemingly endless storm-strewn deserts echo Peter Weir’s The Way Back.

Giancarlo Esposito is one of a plethora of effective secondary characters — casting director Denise Chamain deserves credit for employing so many actors willing to maximise the potential of their bit part statuses. As leader of a ragtag stowaway group, Esposito purveys a mystery that keeps you on your toes (like Rick from The Walking Dead, he also always greets newcomers with three inquisitive questions). There’s an exquisitely queasy turn from Firefly favourite Alan Tudyk — who could do with a wash — though he is part of an unnecessary sideshow plot. Game of Thrones’ Nathalie Emmanuel turns up as a Scorch survivor alongside Rosa Salazar’s strong-willed Brenda.

Having run the maze in sufficient time, they’ve now passed the trials with a splash of merit. It has been an entertaining if unspectacular effort so far. Let’s hope when part three — The Death Cure — rolls into the Scorch, SuperTom and co. finish with aplomb.

Images credit: IMP Awards, Collider

Images copyright (©): 20th Century Fox